Get ready for a different kind of revolution.

Ever since most of the United States’ public schools substituted “keyboard proficiency” for learning penmanship (or cursive, as scholars prefer), a number of teachers – and parents, too – are opting for alternative instruction in how to hand-write.

No duh: The computer and smartphones have impacted language (and, by extension, handwriting) skills; many educators report that kids find it difficult to translate a “tx” or “OMG” into the appropriate scripts. As do quite a few adults.

It’s not so much that cursive – the joining together of letters in a flowing manner – is underused today; rather, its benefits are simply underappreciated. A 1989 University of Virginia study proved that, when terrible handwriting was deliberately improved, so did reading skills, word recognition, composition skills, and recall from memory. Less robust research shows that good cursive leads to better grades … at least, in elementary and middle schools.

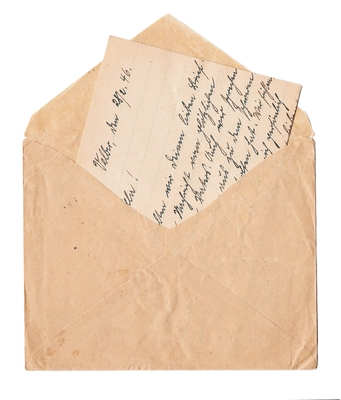

What many miss in this low-key debate is that the handwriting of notes, of postcards, of letters, and of longer missives forges an intimate connection between two people. It’s the kind of bond that many companies aspire to, an engagement between employer and employee. How many managers, in your own career, have penned a note of congratulations or sympathy or, simply, a conversation starter? Do you ever expect to receive personal handwritten notes in home or office mailboxes? Have you? How often in the past year have you deliberately expressed yourself on pen and paper … to colleagues and to staff and to leaders?

What many miss in this low-key debate is that the handwriting of notes, of postcards, of letters, and of longer missives forges an intimate connection between two people. It’s the kind of bond that many companies aspire to, an engagement between employer and employee. How many managers, in your own career, have penned a note of congratulations or sympathy or, simply, a conversation starter? Do you ever expect to receive personal handwritten notes in home or office mailboxes? Have you? How often in the past year have you deliberately expressed yourself on pen and paper … to colleagues and to staff and to leaders?

We’ll admit: It’s all too easy to dash off an e-note, where misspellings are quickly identified – and corrected before sending. And there’s no excuse for being embarrassed about poor handwriting; even a combination of printing and cursive – how most of us write – is acceptable.

Longhand, in short, is tomorrow’s emotional shorthand.